The forgotten Clayton Christensen

How Wall Street's focus on financial ratios can hurt innovation

‘It turns out God has never created data, every piece of data was created by a person. It isn’t real. It’s a representation of phenomena... but there’s a lot about the context in which customers live their lives that doesn’t get incorporated into data of the type most of us imagine.’ - Clayton Christensen

Most business folks have heard of Clayton Christensen or read one of his theories. As heir apparent to Michael Porter, the strategy professor’s writings have become a permanent fixture in business schools and management programs. The theory of disruptive innovation remains one of the most influential theories of the past two decades. More recently, the ‘jobs-to-be-done’ framework has gained popularity and is often the starting point for a ‘learn canvas’ in the startup world.

However, today I want to focus on one lesser talked work of Christensen, one that I believe is equal in importance to his other works. While this body of work doesn’t have a formal name, it focuses on the negative impact of financial ratios on innovation. The idea was originally laid out somewhat vaguely in a 2011 talk given by Clay at a Gartner Symposium. He subsequently elaborated it further in a 2014 HBR article. However, for various reasons, the theory never really caught on and gained as much traction as his other works.

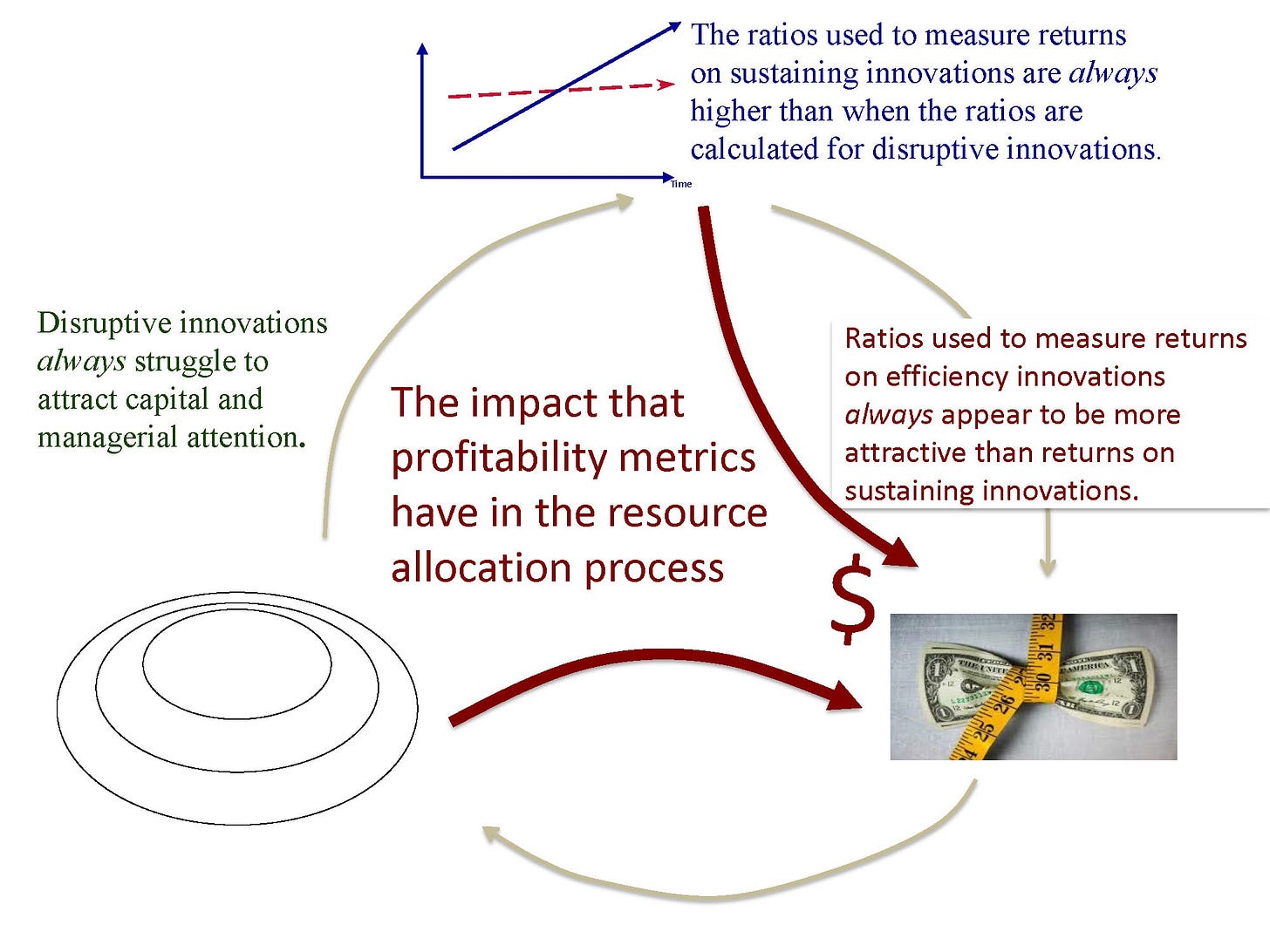

The 60-second summary version of the idea is that innovation is slowing down due to an over-zealous focus by senior managers on financial ratios. This is particularly true in the West where financial markets have tremendous influence on the ‘real’ economy. It is perpetuated by the rise of MBA-type managers who have been raised reading the gospel of CAPM, EMH and formulas like Black-Scholes. Moreover, being proficient in the use of spreadsheet software, they fit innovation ideas into capital allocation framework model and work backwards in making decisions from there. The rise of the management consultant/banker class is testament to the importance these ratios now play in the lives of firms. However, hyper-focusing on ratios like ROA, ROIC and IRR can actually cause even very smart people to make wrong decisions. This final part is likely hara-kiri to anyone who has even taken an introductory finance course. And yet, here is someone claiming it - someone who likely understands this stuff better than most doctorates in finance.

Clay’s argument runs something like this. The standard toolkit of financial ratios is a relatively recent innovation in itself and was popularized by Wall Street in the 1980s to compare stocks of different companies. Along the way, this also developed a new class of managers who realized that such ratios offered a good yardstick to formalize decision-making around new projects. And work well they did as long as ‘sustaining innovations’ are concerned. Innovations like a new sales process, a new software to optimize logistics fall under this category. Such innovations are quite useful broadly as they bring costs down and improve productivity in the economy. The financial ratio toolkit serves its purpose very well as far as evaluating such innovations is concerned.

However, Clay believes that is a separate class of innovations that are severely misrepresented by the use of these ratios. These are market-creating or transformative innovations - ones that often create new product verticals or new classes of customers. Things like the first internal combustion engine, the first microchip or virtual reality all fall under this category. These are clearly different as they enable a series of other related technologies via network efforts and thus unlock significant unexpected economic value. The timeline for such innovations is relatively uncertain and can sometimes be on the order of decades. As such, they require significant investments of capital without any return in the short-run. Here’s a nice graphic summarizing the idea:

As a result, these innovations appear as relatively poor choices under a standard IRR/ROIC/NPV type analysis. Between choosing to invest in a driverless car or in a new CRM system, an IRR analysis will almost always declare the CRM system the winner. And yet, we know the former is one that is 1000x more valuable than the other. However, due to our societal over-reliance on spreadsheets, firms today are vastly under-investing in such disruptive innovations. The huge balance sheets of IBM, Google and Apple are testament to this under-investment.

Clay calls this phenomena an example of the ‘dog wagging the tail’ - i.e. Wall Street analysts driving firm behavior and indirectly setting their policy agenda. He believes that this is a dangerous precedent which could significantly slow down global innovation and hurt firms. He gives the example of the laptop industry to illustrate his point.

In his example, seasoned executives at major PC makers like Hewlett-Packard and Dell chose to outsource manufacturing in the early 2000s to China (Lenovo). The financial toolkit dictated that it would be capital-efficient to outsource the inconvenient parts of the value chain to cheap, low-cost Chinese players. HP and others, guided by an array of consultant and financial advisors, realized that they could shrink their asset bases and juice their ROE by outsourcing manufacturing. Initially, net assets went down and ROA and ROE went up just as standard economic theory would predict. The news was initially welcomed by Wall Street and stocks rose in initial months. Eventually, companies in China achieved scale, went from being pure assembly players and forward integrated into design and distribution. Not only had they mastered the hardest part of the value chain, they realized that they could improve their dollar profits by doing design in-house and setting up their own distribution agreements. As a result, Lenovo - one such one-time outsourcee - is the largest laptop maker in the world today.

It is worth recognizing that the only large company that continues to invest in marketing-creating innovations (Amazon) is one where the founder/CEO shuns ratios. Bezos, instead has a singular focus on a different metric: free cash flow. Here’s Bezos on this topic in one of his shareholder letters:

Which brings me to my last point - I remember reading recently about how some major VCs have stopped using the LTV/CAC > 3.0x metric as a guiding principle for evaluating SaaS deals. The rationale here being that CAC and LTV numbers are inherently unreliable and thus meaningless in a bottom-up context. Instead, these venture firms are now evaluating such companies by looking at the performance o customers via a cohort analysis. A standard table for this looks something like this:

The fact that Stripe has now automatically integrated this analysis into their billing platform might also be reflective of this shifting focus on this new metric. Firms addicted to CAC and LTV calculations should also make the shift sooner rather than later.

Lesson: While ratios like IRR, ROA, ROE, ROIC, P/E offer useful guiding metrics to financial managers, they merely offer one view into the world. Large publicly listed corporates must constantly remind themselves of this and should avoid letting the metrics dictate the talking in boardrooms. Baking metrics and ratios into contracts and compensation agreements can ultimately stifle innovation and hurt shareholders.