Techzadegi: Tech-struck

Tech isn't eating the world, it's eating our minds.

Let’s start with a quick quiz today:

Indulge me as I show you some images. Try and guess the names of the individuals in each picture before reading along and/or clicking in the hyperlinks..

One of these men transformed the global media landscape. Along the way, he also changed the face of modern American politics. The other man is Mark Zuckerberg.

One of these men is the executives of one of the largest funds in the world. His bold decisions have helped shape the direction of global capital markets. The other is Masayoshi Son.

One of these men is the executives of the most valuable carmaker in the world. His company has helped revolutionize not one but two separate industries. The other is Elon Musk.

One of these men is the most recognizable voice in audio. Not only is he among the highest paid figures in media, an endorsement by him can change the fortunes of a political candidate. The other is Joe Rogan

One of these men dedicated his life to philanthropy. His foundation has helped millions of people and he has been a leading candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize on a couple of occasions . The other is Bill Gates

Most people will struggle to identify one of the folks in each of the image set above. So what is common about the folks that are easy to identify? Is it their celebrity? No, the celebrity is merely an output. An output of their shared link to an industry: technology.

Now, the skeptic in you might be having a monologue to the effect of ‘..Ah, but Bill Gates was one of the most recognizable men in the world way before he started doing philanthropy so you’re conflating two unrelated things..’ (For my answer to that, see footnote 1) I ask you to bear with me and hear me out. But first, let’s start with a relatively weird term from Persian.

Gharbzadegi is a complex Persian word. The word is a portmanteau of two words: Gharb (meaning West) and Zadegi (meaning stricken). Translated literally it means ‘West-struck’. It is typically used pejoratively to refer to someone or something that is ‘Westernized’. The term took on considerable importance during the 1960s and 1970s in Iran. The country was then under Shah’s rule and his government had aligned itself with the West through a series of alliances and treaties. While the country was doing well economically and the country was fairly liberal, there was dissatisfaction among Iranian intellectuals. Many of them felt that the country was losing it culture and identity due to an obsession with the West, Western products and Western ideas. Ultimately, the term Gharbzadegi was to have a defining role in shaping the political trajectory of Iran - it was used by Khomeini and Islamists to whip up support during and after the Iranian revolution.

I believe we are all at a similar cross-roads with technology today. What we all face today is ‘Techzadegi’ - i.e. we are ‘Tech-stricken’, tech-obsessed and/or infatuated with tech’. This isn’t the kind of infatuation where we are all addicted to email or our smartphones. Sure, that’s definitely a problem. But this is about the broader problem in our society where everything and everyone is suddenly ‘tech’.

Let me explain further by showing how ‘Techzadegi’ is shaping our world:

Let’s start by considering the ruling class of capital, i.e. our CEOs. But let’s only consider technology CEOs before we contrast them with their peers. Tech CEOs today have cult-like followings which is often equivalent to millions of dollars of earned media for their companies. Tesla doesn’t need to pay for marketing; they have Elon Musk’s Twitter account with 30M+ followers. He can send the stock price of Tesla soaring with a single tweet. He can generate millions in pre-orders for a product that won’t exist for another couple of years (not to mention that this is Tesla’s fifth product launched that is still not commercially available.

Jack Dorsey can send all of Washington in tailspin with a decision to ban political advertisements on Twitter. Imagine the chief of the New York Times getting this much adulation if he undertook the same decision for his publication.

Adam Neumann was famous and giving graduation speeches way before he became notorious for WeWork’s downfall. Spare a thought for IWG’s founder, a company that also leases office space. The only difference being that his company was not a technology company. Even though it leased more space, made more revenue and made an actual profit versus WeWork. And even today, it trades at a valuation ($3.7B) which is less than half of WeWork’s latest valuation.

Even our most well recognized villains are tech folks: Elizabeth Holmes is likely better recognized today than Bernie Madoff despite a few years separating their ‘heist’.

What about other areas? What are our companies, the great bulwarks of capitalism, doing at this uptick of interest in everything-tech? Let me start with an anecdote. I landed at Abu Dhabi airport a few days back and was greeted by posters from Baker Hughes. The posters read something like ‘Baker Hughes is a leading technology company that welcomes you to the UAE’. Which is all nice and chummy except it would be much simpler if they just called themselves oil & gas company. I had to Google that to find it out But semantics matter and how you position yourselves can have a meaningful impact on your public valuation and/or your ability to borrow. It has an impact on private valuations too. Many other companies are also falling to the ‘Baker Hughes effect’ in subtler ways. Companies today routinely name-drop terms like artificial intelligence and digital transformation in their earnings calls. Consider graphs like these:

Now both AI and digital transformation are meaningful forces that are admittedly shaping the direction of business. But the increased mentions of these terms in earnings calls is driven largely by our society’s obsession with the tech. Analysts want to hear executives at these companies tell them about how they’re using AI even if the ground reality is that most of them still don’t use anything beyond GLM - something that has been around for a century.

Tech has also captured the minds of our best and brightest (italicized for irony) students it seems. I remember simpler times when all the cool kids in school wanted to work for Goldman Sachs or McKinsey. Not anymore. Now most kids want to work for a technology company like Google or start their own ‘tech company’. Consider this:

“In 2008, 20% of business school graduates worked in finance and 12% worked in tech, according to the Graduate Management Admission Council, the nonprofit organization that administers the standardized B-school entrance exam. Today, 13% of MBAs work in finance and 17% work in tech, the council's annual survey found.”

What about politics? I also remember simpler times when politicians would spend campaign seasons rallying against big banks and Wall Street. There would be talk of hedge funds and ‘carried interest loopholes’. The current campaign cycle? Entirely different. Now, all the talk seems to be of regulation of Big Tech. Consider this graphic:

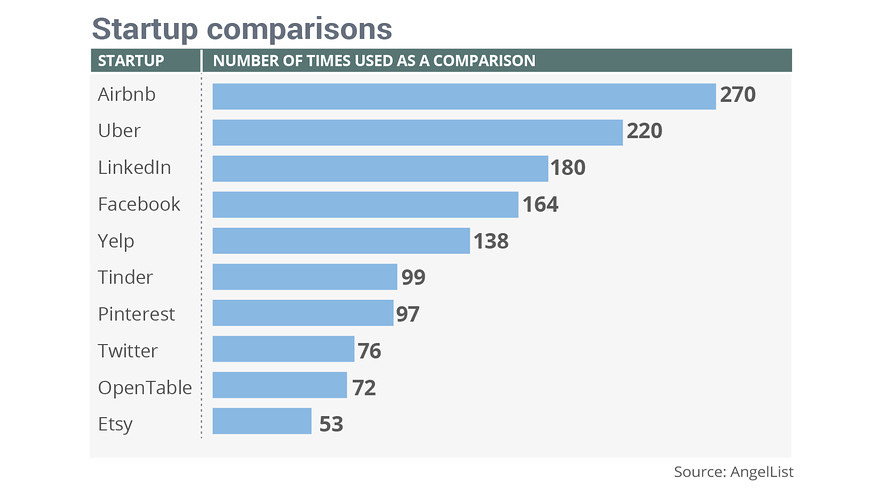

Even our younger companies are caught up in this frenzy. (less surprising, given that most of them start with the moniker of ‘tech start-up’). These companies don’t want to be labelled as the ‘next Walmart or GE’ - i.e. actual industry leaders making billions of dollars of revenues for decades. No, the most popular self-comparisons are again to tech startups:

(Admittedly, the graphic above only shows startup comparisons but anecdotally I can say that no start-up calls themselves the ‘Walmart of X’ whereas almost everyone wants to be the ‘Amazon’ or ‘Netflix’ of some category)

Lastly, today’s technology companies are unique in their ability to take over our language. Tech today is creating verbs that are global in nature. We tweet at people now. We google things. We can Uber to the hotel. And so on. It is forming our adjectives. Being Instagrammable is a huge, huge thing. And well there are way too many nouns to count. Slack, Zoom, Tinder and so on. Or even think of this: people generally say ‘I’m staying at a hotel or I’m staying at an Airbnb’

So, what’s the point? The cultural capital that today’s technology industry has accumulated is perhaps one of the most under-appreciated part of Big Tech’s success. Ask anyone what they think was the most important institution for America in the twentieth century? The likely answer you will be here is the country’s economic might or its military. No, they were important but the real answer is Hollywood. The cultural influence of Hollywood helped assert and maintain American dominance in a way that no swords or sticks ever could. Against a backdrop of rising global prosperity, a whole backdrop of folks grew up consuming American films, listening to rap and watching Disney cartoons. This ultimately made America the place that all immigrants aspired to go to. After the fall of Soviet Union, this cultural influence became almost unparalleled in its might.

But now the nexus of influence is gradually shifting from Hollywood to the technology industry. In the future, Netflix will script the narrative on any issue by choosing the documentary it places on its home screen. Reality TV will no longer be about the Kardashians and Love Island or whatever show E! chooses to show. It will be much larger in nature as tens of thousands of ‘shows’ will be live-streamed on platforms like Instagram, YouTube and Twitch to niche audiences across the globe. The fact that technology companies sit at the cross-roads of this cultural jackpot is what makes them so inherently valuable. That is why Twitter is worth $25B despite barely ever churning out a profit and struggling to grow its userbase in the last few quarters. Sure, the platform might not have figured out monetization but anything that helped jumpstart a few revolutions and helped elect a couple of global leaders is worth way more than 0.125% of America’s annual GDP.

But this cultural capital comes with a dark side. It comes with power at a scale not enjoyed by companies or individuals before. John D. Rockefeller would be worth ~$400B if he were alive today. But his cultural influence would be miniscule compared to most leaders of tech companies today. Steve Huffman, the CEO of Reddit likely has a greater ability to influence political and social movements than Rockefeller or his peers ever had. The same applies to our companies today. Standard Oil might have been broken up into 34 different companies in 1911 due to antitrust reasons. But it had nowhere near as much as social influence as some of our smaller tech companies like Uber and Airbnb. And what about the big ones? Companies like Amazon, Facebook and Netflix are unparalleled in their ability to shape opinions on topics today. Folks like the Koch Brothers get a lot of flak for pouring money into politics. But what’s really powerful about folks like Zuckerberg, Hastings, Dorsey and Musk is that they have a ready-made audience of hundreds of millions ready to chew onto every word they make.

All of this is techzadegi. And every time we like, retweet or click or a story about or favorite tech company or folks connected with these companies, we feed the beast that makes them even more powerful.

Footnote (1): What about Bill Gates vs. Edhi? Well, I get that Gates is more popular than Edhi for reasons entirely unrelated to philanthropy. But the fact that Gates has become the face of philanthropy whereas folks who actually dedicate their whole lives to philanthropy are relatively much lesser known is related to our society’s same obsession with tech. I am sure Bill is a great guy and a net positive for society. But overall, the fact that his image has been fully whitewashed from the 1990s to make him the poster-child for philanthrophy is what bothers me here. I imagine a future where Mark Zuckerberg will also one day become patron saint for many charitable causes. He’s already started by trying to convince us that creating Facebook was really about wanting to help prevent the Iraq War..