Prologue

Imagine a butterfly flapping its wing. What if I told you that this seemingly harmless movement can actually cause a typhoon thousand of miles apart? If that sounds crazy, you won’t be the first one with that reaction. This is the basic idea behind chaos theory* - a field of science that deals with modeling complex systems. In such systems, a few tweaks to initial conditions can have a huge ‘ripple’ effect on events further down the line. This simple yet profound idea has lots of applications outside of science too - notably in business and economics.

Anyways, I’ll show you how an example of how the theory works in the real world. We will start with a seemingly innocuous event in northeast America stretching two decades back. And this one event has ends up heavily influencing the world we live in today. More importantly, it will significantly shape the world for the coming decades. Chaos theory in action. I hope to convince you along the way that world is more weird and interconnected than we really realize. Finally, I’ll make a somewhat dire prediction for the future. But if there is one thing I want you to take away from today’s post - it is in complex systems, predicting the future is a fool’s errand. So take my prediction with a p̶i̶n̶c̶h̶ bucket of salt.

*If you’re curious to learn more about chaos theory, I encourage you to read this great book by James Gleick on the history of the field

Part I: The Formula that changed finance.

January 2000. It was the start of the new millennium. A young researcher, David X. Li, was busy re-working the draft of a paper that he had initially submitted the previous year. In early spring, the paper was finally published in “The Journal of Fixed Income” - an academic journal devoted to papers on financial economics. Titled "On Default Correlation: A Copula Function Approach" - it offered a new approach to modeling risk default correlation between two assets. By using the trading prices of credit-default-swaps (CDS), it vastly simplified the job of calculating default correlation for any asset types. Here is the equation that summarizes the key insight of the paper:

Normally, a paper of this sorts would not get much attention beyond academic circles. But since the author was working at on Wall Street, it managed to get the attention of a few quants. Wall Street had recently been given a new lease of d̶e̶r̶e̶g̶u̶l̶a̶t̶i̶o̶n̶ life with the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999. The quants who pored over the formula realize that they could use it to calculate the prices of a whole host of new-age financial assets. Within a few years, the formula was being used across the financial world. There were murmurs of the author being a future candidate for the Nobel Prize in economics. After all, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes, the creators of the famous Black-Scholes option pricing model, had won one.

On the sidelines, the formula accelerated sales of a couple of financial assets: credit default swaps (CDS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO). If you have seen the movie ‘The Big Short’, these names might sound familiar. These instruments were ultimately what caused the great global recession of 2008-2009. So what’s a CDS? It’s really insurance against the risk of default of any asset. The key difference is unlike rules of traditional insurance, in this case you can own a CDS without owning the asset. But CDS gained in importance not just for their role as speculative assets but in their role as ‘price-makers’ in the financial world. What about CDOs? These are basically just chopped up financial securities. The banks selling these instruments realized that they could slice up individual mortgages into super small portions. They could then repackage these sliced up mortgages into new instruments. While a traditional mortgage reflected the risk of an individual borrower, the risk and correlations associated with such CDOs were much harder to measure. Since essentially each security included a teeny-tiny portion of one individual’s mortgage and since it included mortgages of random individuals from across the United States, the probability of everyone defaulting simultaneously was super low or negligible. Now the logic intuitively makes sense. And the makers of these new class of assets (CDS and CDOs) used these arguments to get AAA ratings for these products. The rating agencies happily complied as they raked in the cash.

There were $920B worth of CDS in 2001. This number had swollen to $62T by 2007.

There were $275B worth of CDOs in 2000. This figure had risen to $4.7T by 2000.

And none of this would have been possible without Li’s ingenious formula. The Gaussian copula become the pricing backbone of this brave new world of these new financial assets. And all was well until it wasn’t. Li’s formula had a drawback and the author had cautioned against its over-use. It assumed a ‘static’ correlation parameter between different assets. Actual market correlations are actually stochastic. They constantly over over time. And yet, the guys selling these CDOs had made this oversight.

Now let’s return to that ‘me-and-my-neighbor-wont-default-together’ argument I made a couple of paragraphs ago. If I default on my mortgage, there is no real reason why my neighbor should default on his or her mortgage. This argument holds if other parts of the economy, notably residential real estate are held constant (or growing). However, quite often the act of an individual defaulting on their mortgage, is caused by a decline in real estate prices. If I default in such a scenario, it is highly likely that my neighbor will default too. Heck - it’s highly likely that everyone in my city or state will default. And the Gaussian copula function failed to properly account for this oddity. Ultimately, when sh*t hit the roof, we were left with the financial crises of 2007.

Part II: Quantitative Easing, Forever.

Our story will move faster and non-linearly through time now. That really is how the real world works.

The financial crises brought about government intervention on a scale not seen since World War 2. Ayn Rand turned in her grave. Keynes rejoiced. (I digress). Anyways, the Federal Reserve and Central Banks responded by setting the policy interest rates at zero. This was to force commercial banks to start lending again. On the side, they also started massive asset purchase operations to buy illiquid assets from the private sectors. The aim was for the government to own them until these recovered in value. This is the infamous ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) of the past decade. QE was supposed to last a couple of years really. And yet it is happening today, a decade after it was first started. Here’s how an eagle-eyed commentator responded to the Fed’s announcement around a new round of asset purchases last week:

So what have the Fed’s actions done? Well, for one it has ‘artificially’ propped up stock valuations. The Obama-Trump stock market boom has really been a Federal Reserve stock market boom. This is reflected in the CAPE ratio which is nearing historic highs (excluding the height of the dot-com bubble)

But the point around interest rate is actually quite important. Here is a related event that happened just last week. Here is how the FT covered it (in one of their backpages):

Now, a country issuing negative-yielding debt isn’t exactly something new. Although because it’s Greece, it’s already interesting. This is a country that less than a decade ago brought the entire Eurozone economy to its feet. And yet, investors are happy to pay it for the privilege of letting it borrow money and return less money later. That a country with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 180% is now issuing negative debt isn’t batsh*t crazy, it is actually a very, very bad sign for the world economy.

At this point, negative-yielding debt isn’t news. Many Western economies (and a few companies) have already issued such debt. Estimates of total such debt ranges from $15-20 Trillion. But the contagion is now also falling to other parts of the ‘real’ economy. A Danish bank recently introduced a negative interest rate mortgage. An offer under which the bank pays borrowers 0.5% to take out a loan.

Now all of this is terrible news on its own. It hurts a lot of industries like banking and insurance. In the case of life insurance, it pretty much kills the traditional business of investing an annuity for x years and paying the saver for his retirement. Beyond these two industries, there are downsides too. Negative rates penalize savers, discourage investment and can lead to a state of permanent economic stagnation (ala Japan’s lost decade) But I’m not here to discuss negative rates but what they do in other parts of the economy. What I want to discuss next is our retirement plans.

Part III: Pension funds go unicorn hunting

If you’re a hardworking, honest citizen, you probably aspire to retire at 60. Maybe live on a farm. And raise a couple of cats. And do the usual things that humans do to find meaning in life. But see our retirement plans rely on a critical component: a well-funded pension plan. But is your plan funded really? And will it be funded in another few decades. We will see.

Let’s start by discussing how a pension fund works. Well, it’s simple really. You take people’s money and you invest it in a mix of stocks and bonds. You earn something like 6-8% annually and get a at pat on the back alongside a nice salary.

Since many of these funds have a long time horizon, they are fairly risk averse. Their asset allocation mix is generally quite conservative. This isn’t your daddy’s hedge fund. Traditionally, a fund allocates something like 60-70% to bonds, 25-35% to stocks and maybe 5% to a ‘risky’ asset class like Private Equity or Venture Capital. Now imagine a world where yields dry up in the fixed income world. To make matters worse, most of the exciting ‘technology’ companies that your friends talk about refuse to IPO and list on public markets now. You have two options:

You sit on the sidelines like a boring hag

You go where the party is

As you might have guessed, post 2008 - fund managers slowly started going where the party was. And here is how this played out in asset allocation terms for the sector:

Now pension is a multi-trillion dollar industry ($20T in the US alone). So a shift from 7% to 20% alone is worth a couple of extra trillion for tech bros. But see pension fund folks are mostly old, finance-type dudes. They couldn’t distinguish an Airbnb from a Juicero. As such, these folks realized that they probably couldn’t invest this money themselves. So they did the next best thing. They become limited partners (LPs) for major Venture Capital funds. And while a lot of this money went to existing funds, a new class of mega-funds ($10B+) was also born. SoftBank is obviously the poster-child of these brash new funds. But there are many others who have kept a lower public profile while continuing to deploy money at Series D/E stage.

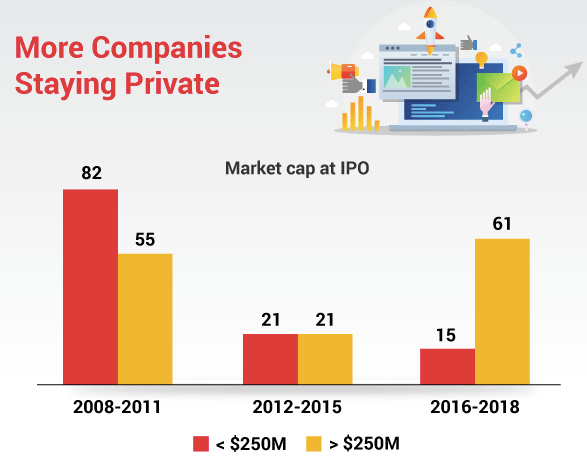

So what did this massive influx of capital do for the technology world? Well, for one it completely messed up valuations. But it also massively increased the total number of startups emerging. And some of these were bad companies with no real business model and just the word ‘technology’ plastered across their S-1s. It also meant a delaying of the ‘time-to-IPO’. Startups no longer felt the need to open themselves up to scrutiny while they are were still in m̶o̶n̶e̶y̶-̶l̶o̶s̶i̶n̶g̶ growth phase. Here is how the numbers look:

Most crucially, these nouveaux riches brought back an ugly practice from the excesses of the dot-com era: companies using capital as a weapon to gain market share. Thus, startups with interesting business models and product-market fit heavily subsidized their services in the hopes of gaining (even more) market share and ultimately being the only sheriffs in town. Uber was the classic example this. Backed by Sequoia and SoftBank early on, it knew that it could stay private for many years and avoid having to deal with public market pressures. Being the largest brand in the ridesharing space, it could outcompete and outlast any local rival in any price war. As such, the company continued to raise successive rounds of private financing at higher valuations. Meanwhile, it continued to subsidize its service and lose bucketloads of money.

When these companies finally turned to public markets, the initial response was less than enthusiastic. In the case of Uber and Slack, it has lead to a drop in post IPO stock prices. In the case of WeWork and Postmates, it has lead to scuppered plans for an IPO alongside significant layoffs. Naturally, many in the industry are now questioning the wisdom of this ‘capital-as-a-weapon’ approach. Others have resorted to generic quips like ‘Markets always have winners and losers’. However, the real losers of this whole saga are not the early investors. Sure, their reputations might have taken a bit of a hit. But Masayoshi Son will still collect just about $1B in management fees annually. Bill Gurley will still be on every founder’s ‘dream cap table’ even if Uber’s share price was to halve tomorrow. No, you see the real losers here are ordinary folks like you and me. But before I tell you why, let’s turn to the final part of our story.

Part IV: The Demographic Time Bomb.

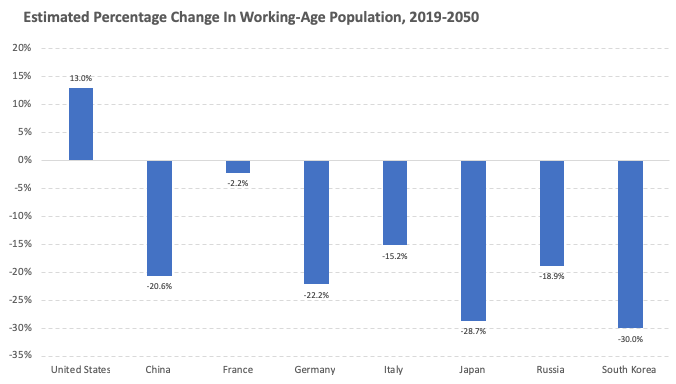

Other than climate change, this is likely the single biggest issue facing our generation. Put simply, we are all sitting on a demographic time bomb. And the bomb is ticking fast. And unlike a change in Federal Reserve policy rate, this can’t be changed overnight. Here’s how the working-age population will evolve in a few major world economies over the next few decades:

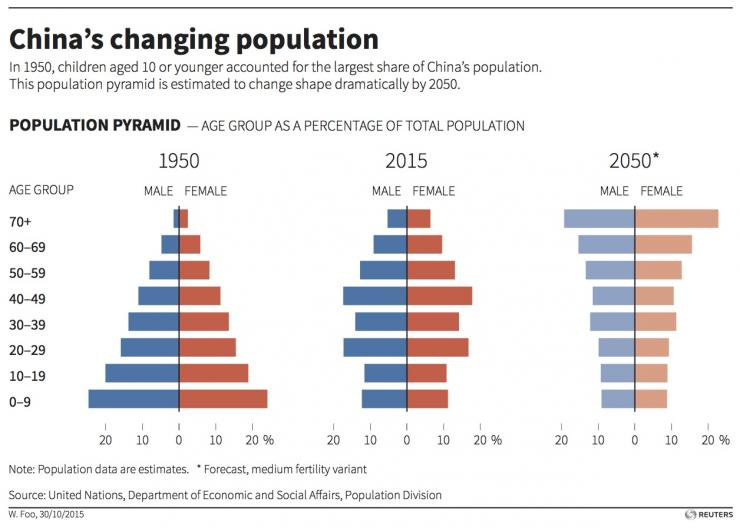

Here’s how the population pyramid will evolve in China, a country responsible for almost a third of global GDP growth over the past three decades.

So other than the United States, most countries in the ‘developed’ world now face a demographic crises. Even in the case of United States, there might be a crises if its politics cause immigrants to leave. This is as immigrants usually have much higher birth rates. A Mexican-American will only stay as long as you keep calling him or her a rap*st. But I digress again.

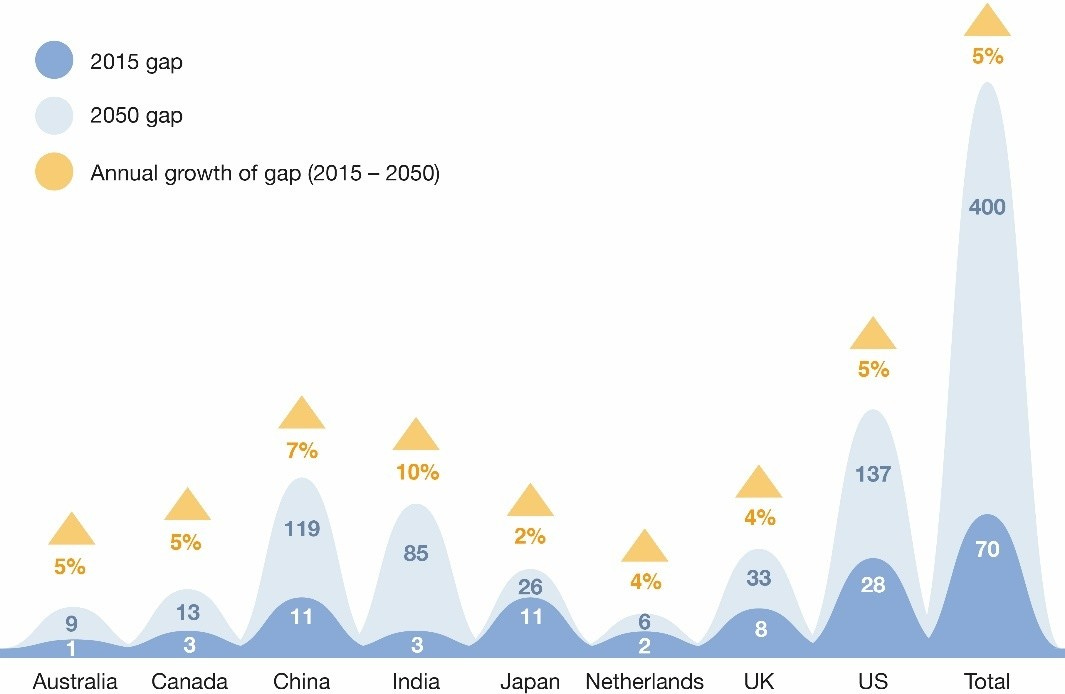

You see, here’s the real kicker. Many state pension funds have often been underfunded in the past. Our parents and grandparents were able to retire and enjoy their pension benefits due to luck + a demographic quirk really. Up until now, the world has had a growing population and a young population. Against a backdrop of economic boom and increase in overall size of labour force, governments were able to tax generation N to pay for the retirement of generation (N-1). And that system worked up until now. But here is how the ‘unfunded pension gap’ will look three decades from now:

So, unless we all start having multiple kids tomorrow, many of us face the looming prospect of turning 60 only to be told that there is no money in our retirement kitty.

Part V: Putting it all together.

So to recap, here is what we covered. We started with an individual drafting a new equation to model financial risk in New York in the year 2000. This lead to the creation of a new class of (mispriced) financial assets against which a borrowing spree took place in the United States. These excesses in the financial sector lead the the Global Recession of 2008. This was followed by years of quantitative easing (2008-2016) and a period of persistent low rates (2009-?). Those rates distorted asset prices and threaten fixed income as an asset class today. Pension funds, desperate for returns, went to Silicon Valley in their quest to unearth the next Uber. While this did give us some great startups, it also lead to another round of excesses - this time in the technology sector. Often times, this was simply a wealth transfer from the shareholders of these companies to consumers in the form of subsidized services. But lo and behold, little did we know that we, the consumers, were technically the shareholders too. Given that our pension fund brethren were now often LPs in these VC funds, it was often we who were bearing the cost when one of these companies lost money. Life came around full circle.

The final part of this story is yet to be written. One thing about complex systems is that they are impossibly hard to predict. That is why most theories in finance and economics remain so shaky and quickly lose predictive power. It is also why even the best of investors beat the market only 55-60% of the time. While I have laid out visions of a dire demographic future, I claim to have no magic crystal ball. However, I do hope I have convinced you of the following:

Seemingly innocuous events can have a huge impact on things far away into the future. A simple statistical equation has changed our world more than a single politician. While we might have had a financial crises independent of this equation, it definitely helped accelerate and magnify the scale of the crises.

Incentives shape outcomes. As Charlie Munger famously said, “Show me the incentive, I’ll show you the outcome”. Wrong incentives lead to the creation of CDOs. Perverse incentives (i.e. fund managers earning fees for IRR > 7-8%) is what is causing an over-investment in the VC sector

It is hard to discern skill from luck. When in doubt, always assume it’s luck. Many entrepreneurs often attribute their successes to luck. However, I sometimes feel that this is sort of a humble brag and just the thing you are expected to say once you’re rich and famous. Luck isn’t about the education you get or the parents you get. Sure, those are important but only in the egotistical, self-centered way in which we humans are wired to think by default. The real role luck plays is in ensuring that all the unrelated forces in the universe align to help outcomes in your favour. In Uber’s case, it wasn’t Travis Kalanick’s background or brains or any easing of laws around taxi medallions. Luck really was the presence of a newly promoted brash crown prince thousands of miles away. A ruler who wanted to modernize his country in part by investing in ‘technologies’ of the future. In Masayoshi Son and Softbank, he found a willing accomplice. His commitment of $45B to Son’s fund was confirmed after just a forty-five minute meeting. $1B per minute. As Son took on Silicon Valley with his warchest, companies like Uber realized that the rules of the game had changed. Forget Gross Margins and EBITDA. Enter revenue growth and # of users. This focus on growth isn’t actually too different from the dotcom era. As luck would have it, just this time there were enabling technologies and wads of capital to sustain this frenzy while the tide was still high.

We need to find a better medium to express the outrage associated with long-term events that threaten our lives and well-being. e.g. climate and demographic changes. The current 24 hour news media cycle is a bad idea. It makes outrage such a regular feature of daily programming that one naturally loses sight of things. Listening to ‘news’ about Trump’s Ukraine call or Boris Johnson’s affair might give us a dopamine hit, but it won’t be in our memory a few weeks from now. You won’t even remember it a couple of years later. And a generation later, most of the world won’t even remember who Trump or Johnson were. However, all of us will still be facing the consequences of high overall indebtedness, demographic shifts and climate change.

To receive more posts like this, sign up for our newsletter!