“Creating the right experiences, and then integrating around them to solve a job, is critical for competitive advantage. That's because while competitors may attempt to copy products, it's difficult for them to copy experiences that are well integrated into your company's processes.” - Clayton Christensen, 2018

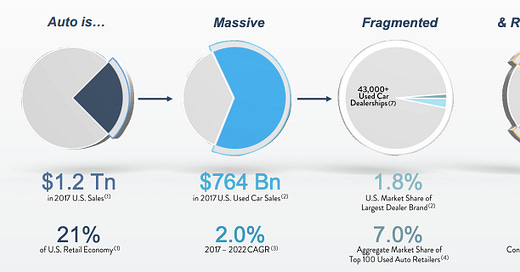

Let’s look at the US car industry, a massive and highly fragmented industry with no clear market leader, poor industry NPS and a poor customer experience overall.

To put some further numbers behind this, there are roughly 63,000 used car dealerships in North America with the biggest player holding 1.6% market share and the top 100 collectively holding only about 7.0%. And the lack of market leadership is even more stark when you size the industry relative to other retail sectors:

The use of digital and internet is everywhere and yet the traditional dealership model still remains the way most people buy and sell their cars. As a result, the experience remains broken.

CarMax, the current leader in the segment, was founded over 25 years ago. The company, with a market cap of ~$14B, has amassed over 211 retail locations across the United States. A typical CarMax store/dealership is 59,000 square feet and is typically located in a metropolitan area.

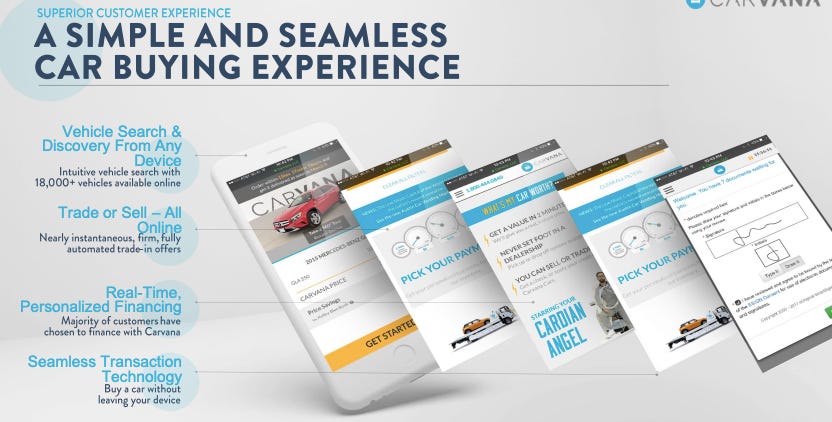

Step-in Carvana, an Arizona-based startup that is looking to upend the industry. Here’s a recent ad video summarizing their unique proposition:

Carvana is basically an online marketplace which aims to provide a fully integrated experience around the car buying and selling process. Central to their proposition is an increased use of technology to simplify and expedite the car purchase process. Additionally, by weeding out middle men from the process, they are able to offer prices that are typically $1000 (or more) cheaper than dealers (including CarMax) and even Kelley Blue Book values.

Here’s how their business model stands versus other industry players:

Instead of large dealership locations, Carvana has built vending machines and fulfillment centers across the United States. Vending machines in particular have proved quite popular with customers and have given the company a lot of positive media coverage and traction. Here’s what one such (patented) vending unit looks like:

It costs them about $5m in capex to build one such vending unit which compares favorably to the unit economics of opening a new dealership (accounting for the lower acreage needed for a vending unit). Anecdotally, the company gets an uplift of roughly 2x in each market when a new vending machine is built and gives the company a lot of earned media in the form of free news and social media coverage. Here’s how the company’s customer penetration graph looked like post installation of vending machines in Nashville and Atlanta:

Carvana is also believed to have a $1000 unit cost advantage vs. brick and mortar dealerships. This is due to ~$250 lower costs for reconditioning and $750 lower costs for SG&A per unit. At scale, analysts expect Carvana to make an EBIT of $1750/unit (which compares quite favorably to the industry leader, CarMax’s, $1000/unit).

Analysts have definitely bought into all the hype with the company’ s market cap of $8.56B (15x trailing 2018 sales) reflective of this collective belief. Here’s one write-up from a bullish analyst on what he believes is the underlying opportunity here:

Having said that, the actual company financials present a much bleaker picture. Here’s what the company’s margins have looked like over the past 5 years:

Remember, the EBITDA figure doesn’t even account for the fact that the company spent $144M on capex in 2018 (a number projected to rise significantly as the company opens more locations). Here are the company’s (aspirational) long-term margins:

While some costs such as advertising have a believable path to being lowered (esp. once compared relative to peers), others such as SG&A don’t pass the smell test. Having said that, even if we take these numbers at face value the high valuation still remains somewhat surprising. The underlying net margins in the business would still be 2-3% once the financing and capex costs are accounted for.

A more likely scenario is that the company at this stage remains a Wall Street darling just because it is a company using technology to upend a traditional industry. The size of the company is still relatively small such that it might soon be a takeover target for a large lender interested in building an auto portfolio and bringing underwriting capabilities in-house. Given that Carvana has kept lending fully in-house and has made a big fuss about its superior risk selection capabilities, the vertical integration might soon pay dividends then.

Lesson:

Take a large market:

Line up a kick-ass team with previous industry experience:

And tell a compelling story around how ‘technology’ is enabling your product to change the customer experience..

..and private and public markets will reward you with innumerable capital, time and momentum to create the next industry giant.

Generating the same hype as an incumbent for a new venture and getting the same buzz, press coverage and media interest is generally much more difficult. However, as the evidence of Amazon, Disney, Goldman Sachs (Marcus), and a few others shows that this isn’t impossible. What is needed is the appropriate structure and right level of disclosures to the market.

Appendix: Carvana’s income statement vs. major competitors: