Algorithms to live by

How the rule of 37 can help us think about product pivots

Imagine this: you’ve just moved to Paris and are looking to lease an apartment. Since it’s the summer, the housing market is pretty hot. You find something you like but aren’t sure if you’ve viewed enough apartments to confirm just yet. Wait more and you could risk losing out on this one. How might you go about picking your best bet? Most people go about this by applying some set of internal rules to the search process. However, it turns out there is an optimal solution to this. Mathematics and computer science have a whole set of problems devoted to this under optimal stopping theory. And one area within that - the secretary problem - suggests that the optimal stopping rule to the problem above is 37%. i.e. the best way to go about the search process described above is to view the first 37% of apartment without committing to anything. After the first 37%, we should settle on the first one that comes that is better than all the existing ones we’ve seen.

This algorithm has wider application beyond housing choice and offers guidance around a whole field of life problems. Want to hire a secretary? Use the rule of 37. Not sure when to stop dating and settle down. Use the rule of 37. And so on. But what is interesting about the rule is that the probability of success (i.e. finding the best house, applicant or mate) is only about 37%. That means even under an optimal decision-making scenario, there’s a 2/3rd chance that we didn’t make the best pick. That is a very humbling statistic. I was personally alarmed when I read this. How could this be? And then I remembered this quote from Daniel Kahneman:

“Despite 45 years of work in the field, I am still inclined to make over-confident predictions.”

If the father of modern decision-making theory still gets it wrong, what chance do most of us have. And yet, most of us act as if we have it right. And when this over-confidence spills into the business world, it leads to disastrous results. From excesses in financial markets to millions poured into ridiculous products, there is no shortage of examples.

But I want to focus on a different set of over-confidence problems. One focused around products and business pivots. Startups pivot all the time. Few people know how many billion dollar enterprise companies started off with a completely different idea. Slack was originally a video game company for its first couple of years. Slack’s error page today is still a homage to its gaming past:

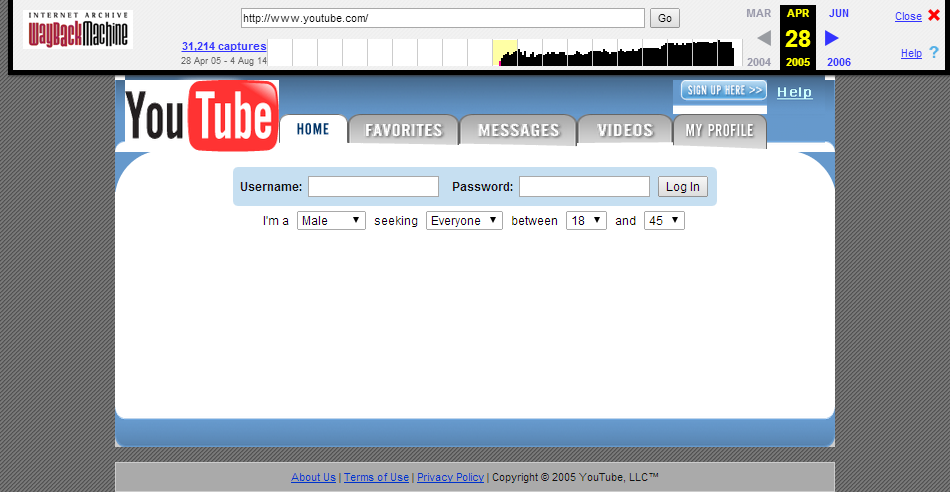

YouTube started as an online dating site. Here’s how it looked in its early days:

And yet, there are many others. Groupon was a social platform for charitable causes. Yelp started as an automated system to ask friends for recommendations. Shopify started off as a snowboard equipment store. Nintendo originally made playing cards. Instagram was a check-in app. Twitter was originally Odeo, a podcasting platform. And the list goes on. And these are just some of the pivots which became public. Early-stage businesses are pivoting all the time. Which is why angel/seed investors focus mostly on the team rather than the idea.

However, public corporations rarely shift significantly in their product ideas. This likely has a few causes:

Cheap availability of capital makes feedback cycles longer so it takes longer before you know whether you have achieved product-market fit.

Public companies have a reputation to protect. As such, admitting defeat and abandoning your original idea to move to something entirely different might be considered damaging to the brand.

Strong focus around cross-sell/up-sell to existing customers. Given that public markets dislike conglomerates with unrelated businesses, pivoting into an unrelated business might be treated with skepticism by sell-side analysts and cause stock price to fall

Lack of direct incentive alignment (i.e. equity) between early-stage employees and business. As a result, there is less of an inclination for anyone to shout ‘The emperor has no clothes’ for something that might not be growing.

Whatever the reason, there is a reluctance among large corporations to pivot with their product and business ideas. This is both dangerous and unfortunate. The Rule of 37 should serve as reminder that we are all constantly wrong. And while it might be important to have grit and persist with things, it is equally important to admit defeat and move on.

To receive more posts like this, sign up for our newsletter!